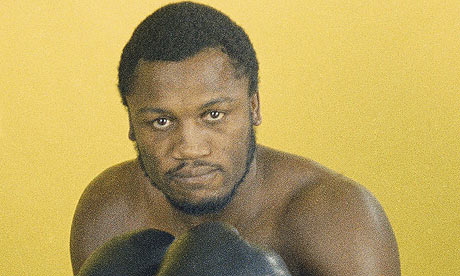

Frazier, who died last night after a brief battle with liver cancer at the age of 67, will forever be linked to Ali. But no one in boxing would dream of anointing Ali as The Greatest unless he, too, was linked to Smokin’ Joe….

In their third and final fight, in Manila in 1975, they traded punches with a fervor that seemed unimaginable among heavyweights. Frazier gave almost as good as he got for 14 rounds, then had to be held back by trainer Eddie Futch as he tried to go out for the final round, unable to see.

“Closest thing to dying that I know of,” Ali said afterward of his experience.

With a few exceptions, boxing — especially in the heavyweight division — seems like a dying art now. Clearly mixed martial arts have cut into its popularity or perhaps supplanted it in the national spotlight (though I have struggled to appreciate the aesthetic intricacies of that sport in my limited exposure to it). I used to be able to chart the succession of heavyweight champions with some certitude, and I couldn’t even tell you which Klitschko holds which belt today.

Maybe I’ve just lost interest. Obviously Manny Pacquiao is sweet, and I know there’s still tons of intrigue in some of the lighter divisions. Whatever. I didn’t set out to write a requiem for boxing.

Maybe I’ve just lost interest. Obviously Manny Pacquiao is sweet, and I know there’s still tons of intrigue in some of the lighter divisions. Whatever. I didn’t set out to write a requiem for boxing.

For a while — specifically, during my freshman year of college — I thought boxing was about the best non-baseball sport imaginable. I was studying empiricism at the time, and I guess boxing seemed like the perfect, stripped-down athletic pursuit: Two guys with very limited equipment beating the hell out of each other to determine who would… I don’t know, secure alpha male status or something.

A couple times a week I went to Finley’s Boxing Club, this almost too-perfect gym above an auto-body shop in Northeast DC, wallpapered in fight posters and soundtracked by an awesome cacophony of ringing bells, whirring ropes, fists pounding punching bags and a boombox blaring soul music. The old trainer guy there — Mr. Finley — said I looked like an actor on a soap opera and called me “Hollywood,” which made me feel awesome.

I weighed 175 pounds at the time — In the Best Shape of My Life, in the parlance of Spring Training baseball. Before my senior year of high school football, when I was hellbent on breaking some of my brother’s school weightlifting records, I checked in at about 230. I switched defensive positions and dropped about 30 pounds over the course of that season. I lost another 10 before I graduated, then 15 more in an ill-fated two-month stint on the freshman crew team.

I watched old fights whenever I could (this was before YouTube), and for a variety of reasons I was drawn to Frazier. For one thing, I had read that he took up boxing to lose weight. For another, it felt like his strengths were some I could emulate: He wasn’t tall, but he was relentless. He could take a punch, and get inside a guy and go to work on his body.

I never got past sparring, but even that is about the most taxing athletic activity I’ve ever endeavored. The boxing priest who introduced me to the gym compared every round to a three-minute sprint. That’s about right. The adrenaline rush of chasing down an opposing running back in football can’t compare to the one that comes from standing in a small ring with a dude who’s trying to punch you in the face.

Oh — I sucked, by the way. Lest you think this is any sort of bragging, I should mention that I normally got my ass handed to me in every sparring session. I often matched up with this guy named Guy, a wiry 6’4″ ex-Marine. He jabbed me to hell, and his left hand was usually strong enough to keep me from getting inside like I planned. But even getting beat down was fun as hell in some masochistic way.

Eventually, I took up more typically collegiate pursuits like drinking and standup comedy, and my interest in dedicating hours of my free time getting beaten up waned. I met Frazier and interviewed a few years later at a charity boxing event in DC featuring then up-and-comer Michael Grant (who, Wikipedia tells me, is still going). Nice guy. Great hat.